It is exhilarating to see the best of anything. For many Leicester schoolchildren the National Theatre’s award-winning production of J B Priestley’s An Inspector Calls will be their first experience of live theatre. (The play is a prescribed GCSE text.) It is unlikely to be their last.

It is exhilarating to see the best of anything. For many Leicester schoolchildren the National Theatre’s award-winning production of J B Priestley’s An Inspector Calls will be their first experience of live theatre. (The play is a prescribed GCSE text.) It is unlikely to be their last.

Before seven thirty there was much excited changing of places and some lack of awareness that a ticket assigns you to a particular row and seat. But as soon as the play began the ghostly street children, disconcerting music and amazing set commanded full attention. Not a fidget, not even a sweet wrapper.

Stephen Daldry stunned audiences in 1992 when he chose An Inspector Calls, written during the Second World War and set before the First, for his National Theatre debut. The play was a repertory standard, almost too familiar to critics and theatre-goers. But he eschewed the staple Edwardian drawing room set for a crazy reduced-scale witch’s cottage suspended in the air above a bleak urban street filled with rolling mist and rain. And he went right back into the text and made vivid its revolutionary message, that we are all responsible for each other.

Up in this tiny lighted house the smug Birling family is celebrating daughter Sheila’s engagement. It is 1912 and mill-owner Arthur Birling (Geoff Leesley) is advising his son and future son-in-law to look after their own and not be influenced by socialist cranks like H G Wells and Bernard Shaw. But then a mysterious inspector calls and calls them to account for their involvement in a young woman’s suicide.

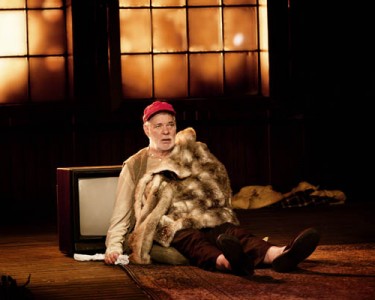

At first the family distances itself from the working class Eva Smith, but the Inspector’s interrogation reveals that they are all responsible for her exploitation, ruin and despair, effectively leading to her death. One by one they descend from their fairy tale existence to the grey cobbled street to face their guilt.

The play is a scathing critique of the hypocrisies of Edwardian English society and Victorian philanthropy – as wonderfully expressed by Sybil Birling (Karen Archer) with her genteel charity committee work – and is seen as an expression of Priestley’s socialist principles: the dialogue between the Inspector and Arthur Birling can be seen as socialism confronting capitalism. It was immediately appealing to a country which had just elected Clement Atlee’s reforming Labour government. The Birlings entertain themselves in their little world, trying and failing to ignore the streets below until their house comes literally and spectacularly crashing down. And because the action doesn’t take place in the cliched meticulous reproduction of an Edwardian room with its mahogany and crystal but instead tumbles down into the street, the accusations and the guilt are for all of us to share.

Many Leicester theatre-goers will be happy that the Curve is enabling the National Theatre to delight this part of the nation. And as the theatre is trying to increase participation it is encouraging to see so many young Asians in the audience.

The Curve until October 1